The Big Five Roundtable brings together four icons of European golf — Sir Nick Faldo, Bernhard Langer, Sandy Lyle and Ian Woosnam — for a rare and richly nostalgic conversation about the era that reshaped the sport.

Guided by Iona Stephen, the players reflect on their parallel journeys from modest beginnings to global success, and on the emergence of the late, great Seve Ballesteros (the only absentee of the group known as the Big Five) as the magnetic force who accelerated European golf’s rise.

Emotional, funny, and deeply human, The Big Five sees stories flow about early struggles on tour, long road trips across Europe and Africa, washing clothes in bathtubs, hitting practice balls with dented range balls, and scraping together winnings just to keep playing. These anecdotes capture both the camaraderie and the grit that defined their generation.

They revisit the breakthrough victories that inspired a continent — from Seve’s first Major in 1979 to their own landmark wins at The Open and the Masters. Each recounts how competition within their peer group pushed them to higher levels, ultimately reshaping Europe’s self‑belief on the world stage and at the Ryder Cup.

Here, we look at some of the key talking points.

Langer: The most unlikely of the Five

Among the Big Five, Langer is the one who insists he is the least likely to have made it this far. His childhood in a Bavarian village of 800 people was as far from elite golf as imaginable — no courses, no culture, no role models. And yet, through a combination of stubbornness, circumstance, and a nine‑year‑old’s fascination with the sight of a few Deutschmarks in his brother’s pocket, he found his way into the game and went on to become the first World Number One and a two‑time Masters champion.

LANGER: My brother, five year older brother who became my manager, one day I was nine and he was 14 so he came home with some Deutschmarks in his pockets and he showed me the money and I said wow, where did you earn that money?, you know, because we’d come from a poor background. And he goes well, I went to caddy, and I said caddy, what’s that?. And he goes well we have a golf course five miles up the road and you know they need boys to pull their bags or carry their bags, whatever. I said can I come with you?

And he goes well I think you’re a little too young for that but I nagged him and nagged him and a few weeks later I’m on my bicycle going to the golf course for my first bag with, you know, as it so happens was the club champion. So I was caddying for a handicap two, not a handicap 32 and he took a liking to this little blonde fellow and he says from now on, you’re going to be my regular caddy and you know that was a lot of fun. But I always say my first love with golf was making money, not playing the game of golf.

Woosnam’s shot-making began with a biscuit tin and a cow shed

Before launch monitors, biomechanics, and data‑driven coaching, there was a cow shed and a biscuit tin hanging from a net. Woosnam’s early practice set-up was improvised, agricultural, and utterly brilliant. It taught him trajectory, feel, and the ability to visualise shots in a way that would later define his career. It also captures something essential about this generation: they learned the game through creativity, not instruction.

WOOSNAM: For me, golf was about watching and learning, then putting it into practice you know. I tell you, like Nick was telling you about hitting golf balls when he was young and on the field and everything. I had to go in the cow shed so I made myself a big net, the cows were there, I’m here, mat there. So I had a tin, in the net. A tin of, a biscuit tin.

FALDO: And you fired it at the tin?

WOOSNAM: And I moved it up and down and I hit it at the tin.

FALDO: Really? To get the right trajectory?

WOOSNAM: To get the right flight so I put it this height, I put it that height.

FALDO: That’s brilliant.

WOOSNAM: So I put it that height and I’d hit with a seven iron, try and hit it, so when I see a gap in a tree now, I can just see what club.

Woosnam wasn’t alone in this either. The Big Five all shaped shots out of boredom, curiosity, and necessity. From Lyle playing around a tree to Faldo on a football pitch, it’s clear that imagination and repitition played a huge part in why so many of them became such compelling shot‑makers.

Langer changed his putter because Seve said so… then won his first tournament on Tour

One of the most charming stories in the entire conversation is how Langer won his first Tour event — and how it began with Ballesteros casually dismissing his putter on the Sunningdale practice green. It’s a perfect snapshot of Seve’s influence: instinctive, blunt, and transformative.

Two weeks before his win, Langer was on the putting green at Sunningdale when Seve asked to see his putter, and walked away after hitting just three shots. Resolved to listen when Ballesteros dismissed it, Langer went to the pro-shop and found a used putter, which he decided he wanted to buy. As it transpired, it had belonged to an 85-year-old lady that had given up the game, so he got it for just £5. He was third that week, second the next, and won his first event the week later at the 1980 Dunlop Masters.

LANGER: Two weeks prior we were playing Sunningdale and I was on the putting green, and Seve walks toward me and says so what are you putting with? I handed him my putter and he hits three putts, hands me the putter and walks away.

I’m going hold on, Seve, what? What do you think about my putter? And he goes, you really want to know? I say yeah that’s why I’m asking, I mean I looked up to Seve. He was maybe the best putter we had at the time and he goes, well, if you really want to know, I think it’s too light and it doesn’t have enough loft. It’s rubbish basically. And he kept walking! So I’m thinking well, if Seve says so, I’d better find a new putter. Straight into the pro shop, I’m mooching around and I see this used putter in the corner and I say can I try this for five minutes? Guy goes, yeah, sure mate, just bring it back and I hit it, and it looked like mine. It was heavier, more loft, make a long story short, I said I want to buy this putter and he goes that was an old lady, she quit golf, she was 85 and you can have it for £5. And so I paid £5, I finished third in Sunningdale, second the next week and then I won my first tournament so Seve, thank you very much.

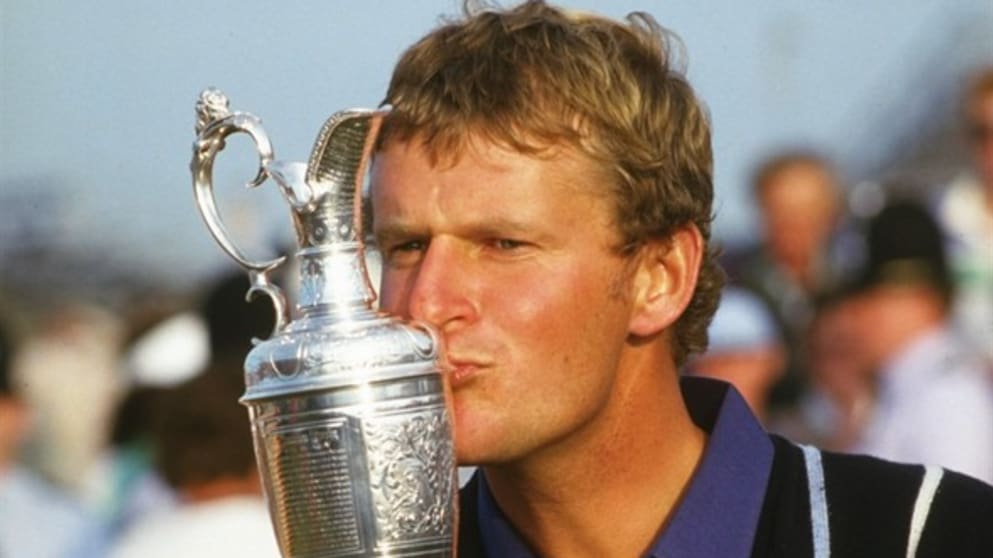

Woosnam gave Lyle a hand-me-down driver after shooting 99 at Royal Dublin, and he went on to win The Open

Less than a month before winning The Open in 1985, the entire of the Big Five were playing in the Carroll’s Irish Open at Royal Dublin. It was won by Seve, with Langer second, Woosnam third, Faldo 18th and Lyle…. disqualified. The official leaderboard on the DP World Tour website has Lyle down for a 99 in the first round, but Woosnam swears it was more -

LYLE: I think we were in Ireland – he’s laughing (speaking of Woosnam) and I shot a 90-odd, I think.

WOOSNAM: I’m sure it was 100. You picked it up. It was a dog-leg around the corner, it was out of bounds, right? It was out of bounds and you decided I’m not going to, and walked in.

LYLE: I was playing a five iron second shot because I’d played an iron off the tee so I’m going to at least try and break 90, I said, and I hit it out of bounds and I said well, Royal Dublin, yeah.

Frustrated, Lyle then put a hand‑me‑down MacGregor driver in the bag — a club passed from Eamonn Darcy to Woosnam to him. It was an act of experimentation, but it became the club that delivered one of the most memorable Open victories of the era.

LYLE: So it just shows you how stupid this game is. You can shoot that and turn it around and then – I used a hand-me-down driver. You gave me that keyhole driver.

WOOSNAM: Oh right, that black one?

LYLE: That Eamonn Darcy had given you, or whatever. You didn’t like it so you said did you want it, kind of thing, did you want it, you can have it. So I thought well it’s a MacGregor driver and I put a new shaft in it and it worked wonders that week at Royal St George's. I got a whippier shaft than his.

Born within a year: A golden generation that drove each other forward

The Big Five weren’t just contemporaries. All born within 12 months of each other, they emerged at a very similar time, on the same tour, under the same pressures, all in their own way and together competing and contributing to European golf’s transformation. They sharpened each other, chased each other, and raised the bar for what European players believed was possible.

This generational synchronicity created a competitive ecosystem, where each one’s success forced the others to evolve and breakthroughs – like Seve’s at the Masters – opened a door.

LANGER: We all came on at the same time… and pushed each other on, I think it made us who we are. Because we had to get better and better because we were playing against each other and we were not just good in Europe. We were good around the world, so we just elevated each other, wouldn’t you think?

WOOSNAM: Yeah, no doubt about it. You’ve got Nick, Bernhard, me, Sandy, Seve, a lot of other players, all playing in the same tournaments and you know to win a tournament was very difficult.

Nowhere is that dynamic clearer than in the Woosnam–Lyle rivalry, which began long before either reached the world stage.

WOOSNAM: I had a person right next to me who was like same age as me, three weeks older, four weeks older. I mean, you know, I had someone, I had a level, I knew what I had to get to to be a top golfer and that was Sandy Lyle because there was no doubt Sandy at 15, 16 was going to be one of the greatest golfers ever to live.

LYLE: I pulled you along

WOOSNAM: He pulled me along so I owe him a lot.

WOOSNAM: Sandy elevated me and it’s like then we elevated each other to go to the next level because we all wanted to do what Seve did in a way and Tony Jacklin and Jack Nicklaus and Gary. We all wanted, and I think in a way that we wanted to elevate that to go to the Ryder Cup so we could challenge for the Ryder Cup and fetch that cup back into Europe and that’s what we really wanted. I know we got our individual things. We all want to be the best player in the world and win tournaments but we wanted to stand there as a European Tour, that we are as strong as America, or our players are as good as America.

Bringing their own range balls, shared rooms, driving in a van, going back to work to earn money… the early beginnings of the European Tour

The early European Tour was a world away from the Tour it is today. With a lot less money and stories of caddie’s losing teeth retrieving golf balls to stories of a 48-hour travel day and eight stops (Langer) and sitting on a plane with golf clubs in the aisle barely clearing the trees (Faldo), the Big Five reflect on the early days of surviving on Tour with plenty of fondness and hilarity.

LANGER: We didn’t go to South Africa or Asia, anywhere, like only Europe and then you know I was 18. I couldn’t rent a car. We didn’t have courtesy cars and so it was very difficult.

LYLE: You had to bring your own practice balls.

LANGER: You had to go by bus or by train unless you had your own car but with my own car, going all the way to Great Britain was complicated, took forever and so the whole thing, I remember the range balls were so bad in some of the courses that we went to. There were these yellow 50 compression and it went like – and you didn’t know was that me hitting a bad shot or was it the ball? So everybody came with their shag bag. So we travelled golf bags, suitcase, carry-on.

FALDO: Two pairs of shoes.

LANGER: Because we brought our own shag bags, we sent our caddies out there to pick them up so any time on any given day you’d be hitting balls with 15 other people and the caddies are out there dodging balls, you know because we couldn’t always hit it right at them.

FALDO: There was a few famous guys lost a tooth or two.

LYLE: You need sponsors, you know, but I made Walker Cup so I got sponsorship from Hawkstone Park. They gave me so much money up front and then I signed up with Dunlop. I signed all three, whatever, there was clubs, ball and clothing with Dunlop. I think that was £1600 they paid me.

WOOSNAM: In my first trips I used to go down to Portugal and used to go Portugal, Spain, Italy, back to Spain and then up to France, whichever way it was, so off I’d go for like four months, three weeks, four weeks in my van. No satnav, not a lot of money so other times you know I’d play in tournaments and then I’d have to stop because I’d run out of money, have to go back on the farm or find a job to work to go back and try - I’d go and play in the Midlands Tour. Funny enough, they used to play some good money in the Midlands so I’d go over there and win. You know I can remember it being like £1000 first prize. It was a lot of money so that would keep me going for weeks and off I’d go in my van, you know.

During his 1985 Masters win, Langer changed his irons after the second round and had what he calls ‘the luckiest break of his career’ at 13

Everyone needs a combination of skill and luck to win a Major. Langer certainly had both at the 1985 Masters. He had decided to change his entire iron set-up after the second round, but it was his three wood that provided the luck just when he needed it on Saturday at the 13th hole.

LANGER: ’85 was my first one. I actually changed my whole set of irons after two rounds and I usually don’t have a back-up set of irons but I probably ordered one for the future and I thought well bring them to Augusta and hit them and see how they go, and I wasn’t going to take a chance putting new clubs into my bag but I wasn’t happy with my iron game the first two rounds so I thought I’ll take a chance, just put them in and that worked out. Two things, I got the luckiest break in my life probably on – and you may not agree because you called me out a few other times but thinking of Wentworth - but on 13 the dog-leg right on Saturday, I’m standing at my tee shot and the distance was a three wood to get to the green and I’m thinking this lie is not good and so, but I realised I’m six shots behind the leader at the time.

I think I have to make birdie here if I want to be in contention, and Peter Coleman, my caddy, gives me the yardage and says, agrees with what I had and I go I’m going to hit three wood and he goes look at that lie, you’ve got to get out of there and well, literally. I say I know but you know we’ve got to make birdie, we’re six behind. So you know sometimes you make stupid decisions in golf or the wrong ones so I hit my three wood, it got about this high off the ground, the whole time, just going like a bullet, heading for Rae’s Creek, yeah. And there’s a little knob in front of Rae’s Creek at the time, they took it away now. It hit the upslope, bounced over the creek onto the green and then I make a 30-footer or 40-footer for eagle. So biggest break I can remember in my life, OK?

Faldo began hitting shots on the school field with a neighbour’s seven and eight iron

Faldo’s path into golf didn’t begin on a course — it began in his living room. He didn’t grow up in a golfing family, didn’t come from a club culture, and didn’t even know the sport existed until his parents bought a colour television when he was 12. That year, he watched the Masters for the first time, and in that moment, he decided he wanted to try golf. His parents booked him six lessons, a neighbour handed him a seven and eight iron, and he started practising alone on the school field. Within three years, he was already sure he was going to become a professional golfer.

FALDO: I was a sportsman looking for a sport. I was good at everything apart from gymnastics, you know, too big for that, you know, and then golf came along. You know things, silly things like we didn’t get a colour TV till I was 12, you know, so that’s when I saw the Masters and I literally said well I want to try golf. My parents went down to the club, didn’t know anything about it, booked half a dozen lessons. That’s how I started. Luckily I had a neighbour who gave me a seven and eight iron, my next door neighbour, you know and I’d start swinging outside every evening and rummaged through the bushes and found 20 balls. My mum was a dress-maker, made me a little bag but I used to sneak over to the school just up the road from me and hit balls down, you know down the football pitch lines and all this sort of thing.

So then by 15, I sat with our employment person and said I want to be a pro golfer and they said only one in 10,000 makes it. That’s what she said. I said well I’m the one! You know, honest, I said I’m the one and I went to the practice ground and again you know I had half a hole. It was 160 yards long, I had one green, one bunker, one flag and then we got bored, like Sandy said, and you ended up you could do this with a two iron. Can I hit a two iron, a loopy thing and that? And you threw balls in the bushes and I was out there on my own. I’m an only child, and so I loved it. I mean I was out there all day. Hey, that’s what made us.

Seve told them to celebrate the ’83 Ryder Cup loss

The 1983 Ryder Cup was a turning point for the European team. Not because they won, but because Seve insisted they celebrate losing by one point. It was the moment belief took root. It was the moment Europe realised they could beat the Americans. And it was the moment the Big Five began to understand their collective power.

FALDO: When we all went to Palm Beach Gardens, ’83, that Ryder Cup was obviously really significant to us and when we lost by one point, and that was a great moment because I was sitting here, Jacklin was there and Seve came in the door and said we must celebrate, this is a victory for us, which was you know, now we believed we could win the Ryder Cup and that’s when we as the Big Five really made an impact, you know, to the European Tour when it was just, just termed the European Tour by then.

LANGER: We were this close to winning in ’83. It came down to the last match, I think it was, Lanny Wadkins and Bernard Gallacher. It was one shot or whatever and even though we lost, we kind of, we all felt you know we can do this because we had lost 27 years in a row.

FALDO: We had half a dozen in the team who genuinely thought we could win, and the other half, let’s just say the other six, weren’t so sure. And then after that, that really flipped. By the time we went to Belfry, ’85, they really was on a “we can do it”.

1987 Ryder Cup — The birth of Team Europe’s modern identity

If 1983 was the beginning of belief, 1987 was the beginning of what it means to be Team Europe. In 1983 there were was a realisation that preparation needed to be better, and by 1987 Europe everything had changed. With the Big Five at the team's core, they travelled together as a team with a shared purpose, and were rewarded with their first victory on away soil - two years after their first win as Europe at The Belfry.

FALDO: We were never prepared, even – we went to Palm Beach Gardens, we had one pair of shoes, right, that’s what you’re given, one shirt. And I said it’s Florida in September, we’ll be soaked. I mean it pours with rain every afternoon. I said we need more than one pair of shoes. We arrived, remember, we had to go into the pro shop to get shirts, remember that?

LANGER: But Jacklin was so good, wasn’t he?

FALDO: Well eventually but he was fighting, he was fighting the - he was fighting it before that, like first captaincy you know and that’s when we said look, we’ve got to be better prepared. We can’t, you know we said we need more kit, the right kit, this sort of thing. I mean even then that was hard work. You know, sweaters would be too long and all sorts of things, I mean, or too short.

FALDO: You know so, you know, and that came along and obviously ’85 and then ’87 was obviously the most, probably the most special, I think. You know we flew over on Concorde and that was, that was fantastic. So we come in because he lands it like a nine iron which is brilliant so that’s another one, you know another one up and I was right behind Tony and we’d got cashmere, we’d got cashmere jackets now, these camel cashmere jackets and we came down the steps and right behind Tony, and Jack comes up and shakes his hand and Jack puts his arm round Tony and feels the cashmere, and Tony’s like – I could do you a good deal, my son, on a bit of you know schmutter. So it was like – another one up! You know so we were playing that game and that’s when the real team spirit started, wasn’t it? Because we stayed together, we had like three houses right on the first tee and then we – and Tony says, right, we are all staying together, we’re in here for the week, nobody’s moving. Eat, drink, sleep, golf. Repeat and rinse as we call it now, where Americans were going off. You know they’d toodle off and go to the cinema, and we thought no, and that’s when, that’s when we really started the kind of the team bonding thing and you know we came in, ate, collapsed, got up next day, off we went again and the atmosphere there was – I can still see it, it was unbelievable, wasn’t it?

IONA: You really feel at this point in the story that things, the momentum was starting to shift. Sandy, what impact did the Big Five, did you guys have on the resurgence of the Ryder Cup?

LYLE: Well, on any team you’ve got the top dogs need to put points on the table and I think we all managed here on this table to put points on there which helps the lower end of the field to pull along, even though we had Europe on our side and Bernhard was my partner and we had some good matches there didn’t we?